Hedy Lamarr: Star of the Silver Screen and Inventor of a WWII Changing Communications Device

March 12, 2020This profile on Hedy Lamarr is the fifth post in a month-long series of profiles about female STEM innovators in honor of Women’s History Month. Check back each weekday to read a new profile.

Hedy Lamarr, born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Austria during 1914, is ubiquitously known as the silver screen sensation of Hollywood’s golden era of film, but her biggest contribution to the U.S. came in the form of a “Secret Communications System”at the beginning of World War II1.

Lamarr’s first film role propelled her into the global spotlight, making her move to Hollywood an obvious place of refuge after a failed marriage with an arms dealer for the Nazis1. She made her U.S. film debut in Algiers (1938), then went on to star in box office hits such as Lady of the Tropics (1939), Boom Town (1940), Tortilla Flat (1942), and Samson and Delilah (1949).

In the midst of her booming career, Lamarr took on a different kind of role—she and her friend composer George Antheil, aided in the Allied Forces effort during WWII.

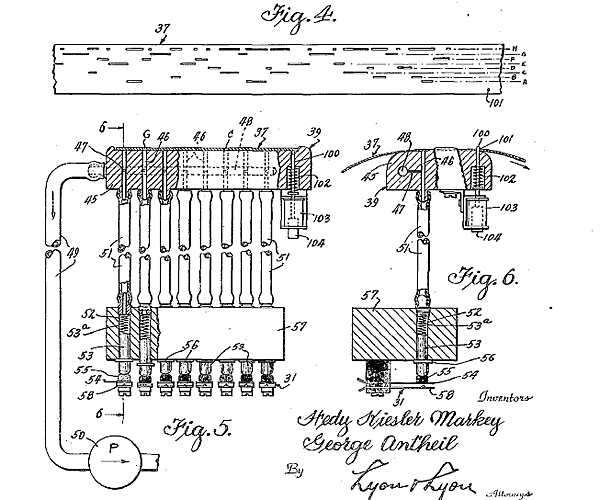

Lamarr learned a great deal of her knowledge on warfare technology, specifically those used by the Germans, from her first husband2. Lamarr brought this knowledge to her partner who in return offered his piano expertise. While these two skill sets may seem incredibly separate and not relevant to war efforts, the duo required both sets of knowledge to create a “frequency-hopping spread-spectrum” system based off the mechanics of a player piano2.

The system was pre-programmed to switch radio frequencies at random intervals so only the desired audience could follow and maintain constant contact, a feature that single-frequency communications lacked2.

After submitting their patent proposal for a “Secret Communication System” in 1941, the New York Times reported that “Lamarr (using her married name at the time, Hedy Kiesler Markey) had invented a device that was so “red hot” and vital to national defense “that government officials will not allow publication of its details,” only that it was related to “remote control of apparatus employed in warfare.”3”

Despite the clear value of this system, the duo had larger visions for this player-piano-based communication method.

Using similarly perforated rolls of paper which control a player pianos, would allow the sequences “to run for a length of time ample for the remote control of a device such as a torpedo” Lamarr explained. 2

Despite the sound logic and demonstrated value of this system, the U.S. Navy rejected their idea, citing the impracticality of placing a player piano inside of a torpedo2. Luckily, future technologists understood that Lamarr and Antheil were merely proposing the implementation of similar frequency hopping devices to protect confidential information, not the installation of actual player pianos2.

Nearly 20 years later the, the U.S. army realized the benefits of changing radio frequencies mid-communiqué by employing electronic “spread-spectrum” technology using the same methodology on military ships3,2. Even broader than military use, Lamarr and Antheil’s innovation were used in modern devices. For instance, cell phones without SIM cards or those that operate on specific plans with Verizon and Sprint, utilize code-division multiple access, more commonly called CDMA. CDMA allows phone users to concurrently occupy the same channel, more technically explained by PC Mag as:

“a "code division" system. Every call's data is encoded with a unique key, then the calls are all transmitted at once; if you have calls 1, 2, and 3 in a channel, the channel would just say 66666666. The receivers each have the unique key to "divide" the combined signal into its individual calls.4”

Despite the less fruitful end of Lamarr’s life, she and Antheil were awarded the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) Pioneer Award in 1997, only three years before Lamarr’s death2,3.

“It’s about time,” Lamarr reportedly said2,3.

In 1997, Lamarr also received the BULBIE™ Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award, becoming the first female recipient of this award referred to as the "Oscars" of inventing2,3.

References:

-

Biography. (2020, March 2). Hedy Lamarr Biography. Retrieved from https://www.biography.com/actor/hedy-lamarr

-

The Atlantic. (2010, September 3). Celebrity Invention: Hedy Lamarr's Secret Communications System. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2010/09/celebrity-invention-hedy-lamarrs-secret-communications-system/62377/.

-

Smithsonian Magazine. (2020, May 23). Team Hollywood’s Secret Weapons System. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/team-hollywoods-secret-weapons-system-103619955/.

-

PC Mag. (2019, May 24). CDMA vs. GSM: What's the Difference?. Retrieved from https://www.pcmag.com/news/cdma-vs-gsm-whats-the-difference.