Machine learning: understanding decision trees

December 21, 2018Dr. Jason M. Pittman, D.Sc., is a scholar, professor, and cybersecurity thought leader. He currently is on the full-time faculty at Capitol Technology University, where he also conducts research on brain-machine interfacing. This is part two of an ongoing series on machine learning.

In my last post, I suggested that machine learning is not machine intelligence.

Additionally, I suggested that machine learning is the instantiation of statistics through algorithms, applied over data sets. As much as we may fear statistics and algorithms, these are approachable, knowable topics. We also get to exercise our working experience with the scientific method. What could be more fun? Little, in my opinion. So let's get started!

What is learning?

A foundational place to start is with an operational definition for learning. In general, I'd argue learning is defined by a combination of action and the object of such action. The object is straightforward: knowledge. The action is harder to pin down but a fine beginning set might be something like create, taught, experience, or acquire. Certainly, there are a multitude of specific incarnations of both our object and action. However, I think we can leave the definition at this level of precision without hampering our progress.

I wanted to start with learning not only because of our topic (machine learning) but also because decisions are an important relational concept. Decisions are how we discriminate between what we know and what we're learning. Further, decisions are how we apply what we've learned to problems. Succinctly, I'd argue decisions are waypoints along the possible solution pathways. Now, there's a rather neat method to represent such knowledge, decisions, waypoints, and pathways relative to a stated problem.

Trees

Trees are a geometrical framework capable of representing waypoints (nodes) along pathways (branches) relative to a stated problem (root). While some of the terminology is botanical in nature, I assure you the trees we use are anything but. Let's look at an example.

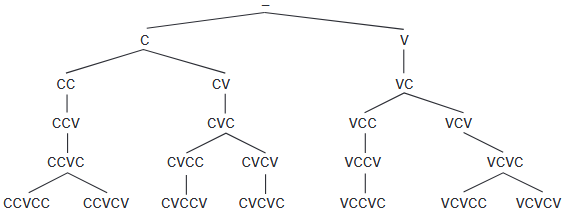

Here, we have a tree representing the number of ways we can build five-letter words using the consonants (C) and vowels (V) from our English alphabet. Trees typically include rules as well. In fact, our Building Words example has three rules: (1) no double vowels, (2) no triple consonants, and (3) two adjacent consonants must not be the same (e.g., ZZ). Pretty neat, right?

Decision Trees

I think decision trees are even neater. These are trees that encode decisions as nodes. To be clear, decisions are a combination of questions and guesses. The questions must be answerable through a yes or no in this case, which seems overly simplistic, but we can learn quite a bit by posing such inquiries. Imagine having a conversation with a friend; that's what a machine learning algorithm is doing albeit with itself and the input data.

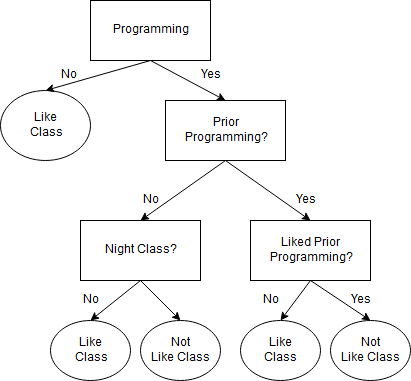

The self-conversation works by situating questions as nodes, possible outcomes as branches, and answers as leaves. Thus, decision trees give us a means to map binary classifications. In fact, this is precisely how we can have seemingly intelligence recommendation systems. Let's take course recommendations for example.

We want to know if a given student will like a specific programming class. We can encode the decision tree as follows.

The basic idea is that if you've never had a programming class and the specific class being examined isn't a night session, you'll probably like it. On the other hand, if you've had prior programming classes and you didn't like them, you're unlikely to like the one in question.

Such decisions can be programmatically instantiated in a straightforward manner. Further, the programming can be such that the system learns to recommend classes to students.

Tune in next time for some programming examples and more machine learning discussion!